David on Technical Topics – Armagnac, A Brief History

There is something unusual occurring in the region of armagnac, the people are Gasçons but the closer you get to the centre, around the small town of Eauz, the more they refer to themselves as Armagnaçais. But whatever they call themselves, they are warm and friendly, lovers of rich food and drink especially truffles and ‘foie gras’, and inhabitants of a rural paradise unspoilt by urban sprawls. The region is tucked away about a hundred miles south of Bordeaux. It stretches back from the sands of the Landes through a series of gentle valleys, which have none of the grim monoculture that marks other vineyards, and provides a most agreeable and varied vision of rural bliss.

However good the area and people, the region is far from the ports and unsuitable for an internationally traded spirit. Armagnac was and remains a reflection of French individualism where its merchants are united as a community and unlike the Cognaçais, still regard themselves as the same class as the growers. By itself individualism would not be of sufficient interest to them but when teamed with a drink as exciting as Armagnac, a unique situation is created. At its best armagnac offers a closeness to nature, a depth of fruit and warmth and a range of vintages that even the finest cognacs cannot match.

In all probability the Armagnaçais were distilling brandy two hundred years before cognac was made, the process being brought over from Africa by the Moors who had used distillation for making perfumes. The spirit produced around the towns of Auch and Bayonne was a local speciality which by the 16th century, had become known as armagnac. But the Armagnaçais lacked the spirit of openness and commercial aggressiveness that those making cognac further north were already exploiting in their trade with the Dutch, English and Irish from the port of La Rochelle. As a result, armagnac did not compete as a rival to cognac in the market that counted – the fashionable society of ‘Restoration’ London – and so it became submerged in the mass of brandies from Bordeaux and Nantes which were considered inferior.

By the nineteenth century armagnac was rescued from its rural seclusion by two dramatic developments. The first was the invention of the continuous still which was essential for extracting armagnacs’ particular qualities from the sandy soil and the second, was that many canals were opened enabling the wines to be transported to the port of Bordeaux.

By the nineteenth century armagnac was rescued from its rural seclusion by two dramatic developments. The first was the invention of the continuous still which was essential for extracting armagnacs’ particular qualities from the sandy soil and the second, was that many canals were opened enabling the wines to be transported to the port of Bordeaux.

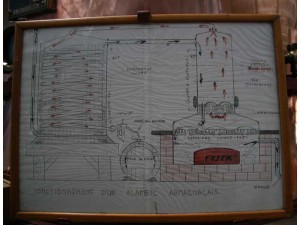

The continuous still, perfected by a peasant by the name of Verdier, retained more of the essential elements in the wine than did the orthodox small pot stills used in cognac. Perhaps more importantly, this still was more easily transportable from one grower to another. Since many of the growers owned only a few hectares of land and simply couldn’t afford to have their own still, this was a necessity. The continuous still provided the Armagnaçais with a raw brandy which was capable of development, in time, into an even more complex spirit than cognac. Although the new still created some initial roughness and woodiness, these effects were overshadowed by the more defined fruity flavours that emerged from using a lower distillation range.

The continuous still, perfected by a peasant by the name of Verdier, retained more of the essential elements in the wine than did the orthodox small pot stills used in cognac. Perhaps more importantly, this still was more easily transportable from one grower to another. Since many of the growers owned only a few hectares of land and simply couldn’t afford to have their own still, this was a necessity. The continuous still provided the Armagnaçais with a raw brandy which was capable of development, in time, into an even more complex spirit than cognac. Although the new still created some initial roughness and woodiness, these effects were overshadowed by the more defined fruity flavours that emerged from using a lower distillation range.

Read more Technical Topics on our Brandy Education page.