What is White Armagnac?

When you think of Armagnac, the image that usually comes to mind is a golden-hued brandy, aged in oak barrels and enjoyed by the fireside. However, Armagnac begins its life as a clear spirit, known as Blanche Armagnac. This unaged ‘eau-de-vie’ is a crystal-clear distillate made from white wine, using a blend of up to ten different grape varieties, most commonly Ugni Blanc and Colombard.

Blanche Armagnac, such as Blanche de Cassagnoles, is intensely aromatic, offering fresh and vibrant flavours that are not found in its aged counterparts. Upon distillation, it carries fruity and floral notes of pears, white peaches, Granny Smith apples, jasmine, and lime flower, combined with a hint of spice.

Blanche Armagnac offers a new perspective on this traditional French brandy, with its lively and youthful character. It is incredibly versatile and pairs beautifully in cocktails where its delicate fruitiness and floral nuances can shine, as seen in the 18.50 recipe. For those seeking to explore Armagnac beyond the traditional oak-aged varieties, Blanche de Cassagnoles is a wonderful Armagnac for cocktails.

Created by Francesco Turrini from Milk & Honey, London, the 18.50 Cocktail perfectly showcases the versatility of Blanche de Cassagnoles Armagnac, highlighting its fresh and aromatic qualities. This delightful autumn blend combines the fruity and floral notes of white Armagnac with the rich, complex flavours of Lillet Blanc and Campari.

18.50 COCKTAIL

Ingredients:

- 60ml Blanche de Cassagnoles Armagnac

- 20ml Lillet Blanc

- 10ml Campari

- 5ml liqueur

- Orange zest

- Ice cubes

- Maraschino cherry (for garnish)

Method:

- Pour the 60ml Blanche de Cassagnoles Armagnac, 20ml Lillet Blanc, 10ml Campari, and 5ml liqueur into a mixing glass.

- Fill the glass with ice cubes and stir gently for around 30 seconds to chill and combine the ingredients.

- Strain the mixture into a pre-chilled glass.

- Express the oils from the orange zest by twisting it over the glass, then discard.

- Garnish with a maraschino cherry for a finishing touch.

This cocktail is an elegant harmony of bitter, sweet, and fruity notes, making it an ideal choice for those crisp autumn evenings.

The Blanche de Cassagnoles Armagnac brings a fresh, pear-like quality that complements the herbal and citrus layers of Lillet Blanc and Campari.

Just like in Cognac, the Armagnac region suffered from the severe spring weather with the heaviest rainfalls recorded since 1952! Thankfully the barometer has now stabilised and trellising has begun. This essential activity supports the vegetation ensuring good aeration of the grapes and minimal shoot damage by wind. Ripening is also optimised, as leaf exposure to the sun improves and thus, encourages photosynthesis. Of great ecological importance is the efficiency of phytosanitary treatment – the arrangement of the leaves on trellised plants helps this to improve. Finally, trellising also facilitates passage between the vines reducing time spent on viniculture and therefore crop costs. The recent good, stable, summer weather has ensured that this year, the budding and general well-being of the vines are exceptional. Very good news for the 2018

Just like in Cognac, the Armagnac region suffered from the severe spring weather with the heaviest rainfalls recorded since 1952! Thankfully the barometer has now stabilised and trellising has begun. This essential activity supports the vegetation ensuring good aeration of the grapes and minimal shoot damage by wind. Ripening is also optimised, as leaf exposure to the sun improves and thus, encourages photosynthesis. Of great ecological importance is the efficiency of phytosanitary treatment – the arrangement of the leaves on trellised plants helps this to improve. Finally, trellising also facilitates passage between the vines reducing time spent on viniculture and therefore crop costs. The recent good, stable, summer weather has ensured that this year, the budding and general well-being of the vines are exceptional. Very good news for the 2018  Armagnacs are the earliest examples of distilled wines known in France. Traditionally they are made using the Folle grape although others, including Colombard, Ugni Blanc and even more recently, the Baco all contribute to its flavour. Initially distillations were on a pot still but by the 19th century the continuous still was more highly favoured. The distillation process of armagnac allows the spirit to be distilled at a much lower alcohol content range than that of its big brother cognac, produced 100 miles to the north. The lower range produces a greater fruitiness (but less refined) flavour in the spirit.

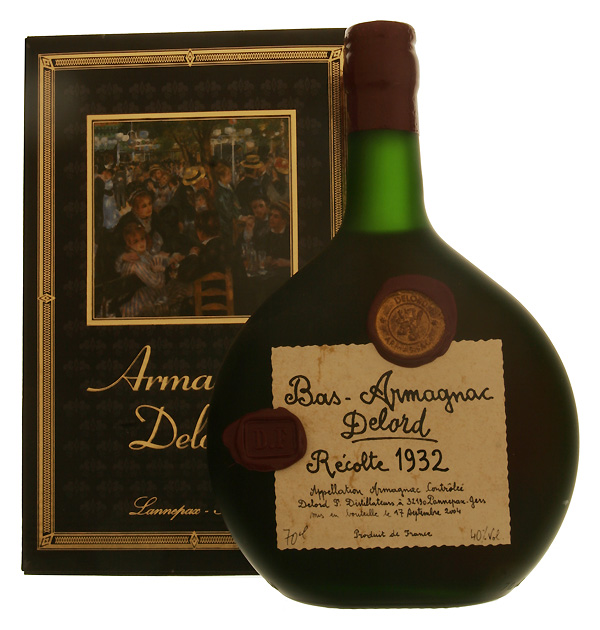

Armagnacs are the earliest examples of distilled wines known in France. Traditionally they are made using the Folle grape although others, including Colombard, Ugni Blanc and even more recently, the Baco all contribute to its flavour. Initially distillations were on a pot still but by the 19th century the continuous still was more highly favoured. The distillation process of armagnac allows the spirit to be distilled at a much lower alcohol content range than that of its big brother cognac, produced 100 miles to the north. The lower range produces a greater fruitiness (but less refined) flavour in the spirit.