It is hugely unfortunate that most people who drink brandy derive only the mildest pleasure from the experience provided for them by experts with generations of family understanding and knowledge to create what in every case is a totally unique experience. How nice it would be if we could all enhance our knowledge and understanding of the drink sufficiently to make each tasting a truly great and memorable experience.

Perhaps part of our problem is that so many brandies have such minimal differences in taste that even for experts it becomes difficult to associate an individual brand with a specific style or flavour. Indeed, the cognac market has, over the years expanded to such an extent that it has become necessary for the big houses to blend thousands of individual and very unique qualities together to meet with market requirements. Any differences are in many cases only detected by the level of sugar syrup added to hide the fiery nature of the increasingly younger cognacs used in the blend.

This generalisation of flavour can also be applied to grape brandies where even larger levels of additives are added to even younger distillations which have in the majority of cases enjoyed only a year absorbing the oak tannins from a barrel. Perhaps armagnacs, for reasons of their smaller markets and the greater range of competing producers, and to a lesser extent calvados, have managed to maintain the individual characteristics so richly desired, having been kept for many years in barrels as intended by their makers. Our world of commercial greed has destroyed large parts of our enjoyment and reduced the potential opportunity for us to recognise the enormous range of individual styles and flavours that were created for our benefit.

In the world of cognac there are approaching 5000 individual producers, each making what they perceive as the finest cognac available. Many of them are not, but their knowledge of others is so limited that they have no measure other than that which is provided for them by the authorities and, even if they did have a measure, their interpretation of quality would be based only on the family style. Only by objective tasting of thousands of different cognacs can one analyse the true quality of their offerings and create a definitive guide to cognac greatness.

Very much like the individual cognac producers, our individual perception of what we like is developed over time and is largely developed by the food and drink we have become accustomed to since birth. These tastes are determined by receptors in our gustatory system, we call them taste buds, we have around 10,000 of them, mainly on the tongue but also on the palate and on the back of the throat. But if we have a lot of taste buds our sense of smell is part of our olfactory system and is far more complex with over 100,000 nerve fibres that connect to the olfactory bulb in the brain. It is of course the brain that becomes trained to the sense of smell and taste that determines what we like. We see families who are brought up on diets of chips and burgers yet find the flavour and smell of potatoes and meat disagreeable since they have never experienced the real foods. Fortunately, our receptors become used to alcoholic drinks at a much later stage in life so our preferences can be more easily moulded to our preferences from bad to good.

There are of course many views on our perceived level of goodness, these are not levels that we can score on a measure of 1-10 they are differences in our individual likes and dislikes and probably developed at earlier stages in our lives when we have experimented with different flavours.

The senses of smell and taste are linked and we can often associate similarities of the senses but it is difficult to form any conclusive evidence of chemical connections between them. There is no general agreement as to primary odour as in the case of the primary tastes of sweet, sour, salty and bitter so to a degree, smell and for that matter taste have become partly subjective. However, many will agree on some basic aromas such as vanilla, lemon and mint which are detectable with our joint senses as well as those that can only be detected with one sense such as tar wood and dried walnuts.

Most of our taste buds are on our tongue. The back of the tongue has larger taste receptors than those at the front but the sensation of tasting can be detected all over the mouth. The tip of our tongues mainly detect sweet and salty flavours whilst the sides are more associated with sour and salty flavours and the region around the tonsils detect the bitter tastes. Many cognacs and brandies have extremely complex flavours and some tastes can be detected on several parts of the tongue. The tasting experience is further complicated by the strong spirit, cognacs must be at least 40% abv by law and some can be stronger.

Professional cognac tasters will look for balance in a cognac and one with a good balance will often have an evenness of flavour that can be detected on most areas of the mouth, this should not be confused with strength as some cognacs can actually have increased flavour with increased strength, this however is not usually the case. Cognacs are double distilled and cognacs made for the major houses are usually made on large onion shaped stills which will allow the spirit to drip back into the boiler, in effect being distilled for a third time, thus creating a greater level of neutrality, usually causing an aggressive sensation on the front of the mouth and a non-distinctive sticky neutral flavour. This is particularly true of VSOP and XO blends from the big houses where in many cases as many as 3000 cognacs are mixed to make a single genetic blend.

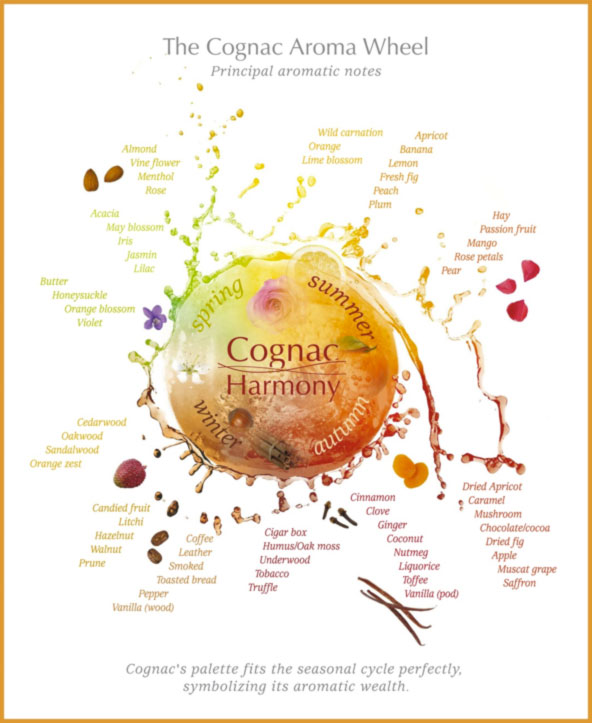

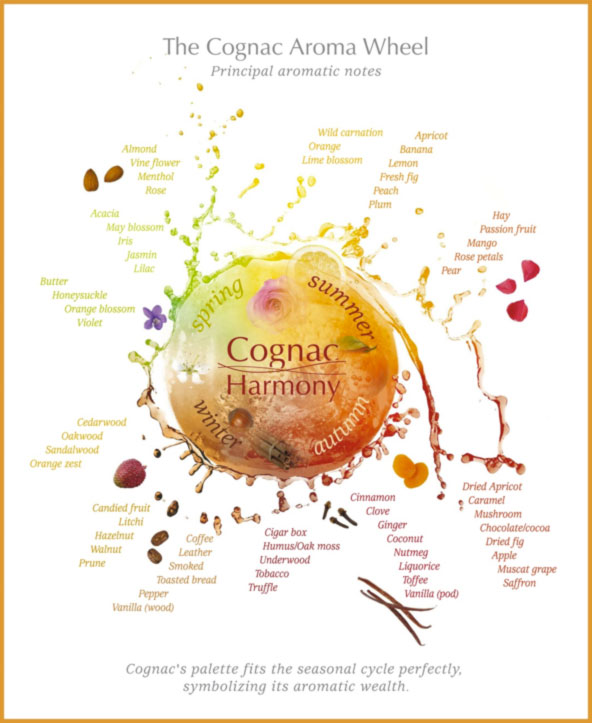

Let us consider the mechanics of tasting and the stages we need to consider before we start. A useful tool we can use to identify different aromas and tastes can be found at the back of this document. It was composed by a team of expert sommeliers brought together by the Bureau National Interprofessionel du Cognac (BNIC), the controlling body of the cognac industry. There are a number of stages we should consider before we start, these are as follows:

1) The glass

2) Pouring and preparing

3) The colour

4) Appearance

5) The nose or aroma

6) The taste

7) The balance

8) The finish

Let’s look at these in greater detail.

The Glass

The traditional brandy balloon is not the ideal shape for tasting a strong spirit and is widely regarded by the French as only suitable for putting your cigars in although a small balloon can be used with a moderate degree of success. Most commonly used in the industry is a small tulip shaped glass, similar designs are also used for tasting whisky. Brandy balloons are not ideal as they allow large quantities of the alcohol to collect on the surface of the cognac blinding the aroma of the brandy. The tulip shaped glass only allows a small surface area of the cognac and the narrow top ensures that the aroma is focused in a small area.

Pouring and Preparing

Many cognacs are sold in attractive carafes and decanters but what is good for the eye is not always good for pouring as many can have a wide rim on the top adjacent to the outlet and unless one is careful they can cause drips to occur. When using a tulip shaped glass, it should be filled to about one third full so as to allow enough room for the cognac to be gently rolled around the inside of the glass. Unlike wines, cognac is a strong spirit and swirling the cognac around the glass is a bad practice as it releases the alcohol which will sit on top of the brandy and blind the aroma. Allow the brandy to stand for a couple of minutes to allow the aromas to develop in the glass ideally on a white surface so that you can observe the colour through the glass.

Colour

The colour of a cognac can depend on many factors and is not generally dependant on its age. All cognacs are first stored in new oak usually for a period of between 6-12 months although some can be stored for longer periods depending on the needs of the producer. New oak has a higher level of tannins and the new spirit will absorb the colour more readily than it does from the old oak where the cognac will spend most of its life whilst in the barrel. The size of the barrel and where it is stored will also have an influence on colour as different cellars have different levels of moisture and damp barrels will tend to slow the passage of the spirit through the wood allowing a greater time for the cognac to darken, a process which can take fifty or more years for the cognac to mature naturally, developing its own distinctive golden colour.

Recognising the colour of a cognac is the first big clue as to what it is going to be like when we come to taste it. Colours can vary from a light straw to almost black but many of the finest will have a range of colour from a mid-gold to a deep gold, usually with a tiny hint of grey. A red hue will indicate the use of caramel, an additive often used to add colour to young cognacs to provide the false appearance of age and commonly found in XO cognacs from the big houses where barrel ageing is usually only for between 8 – 10 years. Very light coloured cognacs tend to come from the top cru, Grande Champagne, where cognacs usually age very slowly but very dark cognacs often indicate a longer ageing in new oak, this provides a burnt oak and usually very fiery flavour.

Appearance

Ones awareness of a fine cognac is often first established when it is poured into the glass. Colour is clearly a factor but the cognac should be alive in its appearance and creating a feeling of wanting to taste it. In a few cases cloudiness can be observed, perhaps where a small quantity has been left in the bottle for a long while and the alcohol has reduced significantly. Well matured cognacs can often leave longer lasting legs inside the glass after rolling it round the sides. A good cognac should be clear and bright and presenting an image of substance in the glass.

Nose

It should be remembered that aroma provides us with around 50% of the pleasure we find in a glass of good brandy, it is important to try and identify the smells in the glass before we drink it as understanding this helps our perception of the drink. The term “nose”, is often used instead of aroma by professionals as it is the olfactory senses that provide the first real indication of our liking for the brandy and this is found by bringing the noble spirit to the nose. It is best to bring the cognac to the nose slowly to provide a gradual indication of its quality aroma and style. Of course the aroma is also going to provide a good indication of the flavour of the cognac and much can be gained by the complexity of the aroma, indeed the complexity often indicates the quality as good cognacs will have aged for long periods and a whole range of different aromas can be detected in those that have been in oak barrels for long periods of time. In some rare but very fine examples, as many as forty or fifty different aromas can be detected but to find these it may be necessary to sit with the glass under ones nose for several hours. The aroma of caramel is not usually a welcome smell as this will indicate the presence of caramel and sugar syrup often used in young highly blended cognacs. It is often wise to write down the aromas you have found in the glass and this can be helped by using the tasting chart at the back.

Taste

The gustatory systems in our mouths provide us with the main clues as to the quality and desirability of the cognac or brandy in the glass. When we smell a fine cognac we often develop a perception of its taste. This is not an illusion, it is a very real indication of the quality of the brandy and the more different flavours we can detect, the older and usually better quality the cognac we have in the glass is.

We need to judge the taste by the effect a brandy has in our mouths. Taste can be detected by the taste buds on our tongues, at the back and on the roof of our mouths. When we take the spirit into our mouths we should have enough to roll around so that every part of our mouth comes into contact with it. This enables all our taste receptors to come into contact with the liquid, Nick Faith, a well-known author of cognac books says that you should chew the cognac and certainly this is a good way to find the flavours in your mouth. Different types of flavour are usually detected in different known areas, for example, sweet flavours are most common on the tips of our tongues but sour flavours are further back. Larger taste buds in the back of our mouths detect salty flavours whilst bitter flavours are most clearly identified near the tonsils. Many very fine cognacs however are so complex that the flavours become muddled and overlap the main taste areas. Writing down the flavours found is a good way of identifying the tipple in you glass and again this can be helped by using the aroma and taste chart at the back.

Balance

Unlike tasting wine, complexity in a spirit is a good measure of quality. Highly complex cognacs or brandies provide an all over balance of flavour on every part of the mouth. If one can only detect sweet flavours it is unlikely that the cognac has any length or quality as it will also most likely have a fiery effect at the front of the tongue as well. A brandy with a good balance will also have many different flavours that can be detected in several parts of the mouth. Aggressive and fiery sensations are usually the signs of poor balance but one must be aware of the strength as some cognacs can be at their best with a higher strength and this can often be confused with poor balance. Some cognacs that have been distilled in small and narrow stills can often have enhanced flavour complexity when consumed at a higher strength but in most cases higher strengths only mask the flavour.

Finish

The period of time the cognac or brandy can still be tasted after drinking can again be attributed to its quality. Well made and aged brandies will have greater taste and presence in the mouth. This enables the flavour to linger longer usually finishing at the back of the mouth and in some instances for many minutes. One of the longest and finest finishes is from cognacs made in the Grande Champagne where citrus flavours can be detected on the tail. Various parts of the cru can offer different flavours but those of grapefruit and orange peel are most common and often a delight to encounter.

Note: When tasting multiple cognacs or brandies do ensure that you spit each out after tasting then wash the mouth with water to provide the best opportunities to taste those that follow.