Armagnac Crus

Armagnac is produced in the south west of France in the departments of Gers and Landes in the region known as Gascony. The region has very little industry and the landscape is relatively flat, very green and the people are friendly, living an altogether quieter life than those in Cognac to the north. Indeed, most of the land is given over to agriculture and perhaps well described by Nick Faith, the famous writer on French Brandies, as the land of Fois Gras. An ideal base for armagnac crus.

Armagnac is produced in the south west of France in the departments of Gers and Landes in the region known as Gascony. The region has very little industry and the landscape is relatively flat, very green and the people are friendly, living an altogether quieter life than those in Cognac to the north. Indeed, most of the land is given over to agriculture and perhaps well described by Nick Faith, the famous writer on French Brandies, as the land of Fois Gras. An ideal base for armagnac crus.

The climate is perhaps a little warmer than in Cognac but still enjoys the temperate conditions so necessary for growing grapes. These are made into wine and then distilled into the oldest spirit in the world, armagnac. It was perhaps made famous by the French musketeer d’Artagnan and immortalised by Alexandre Dunas.

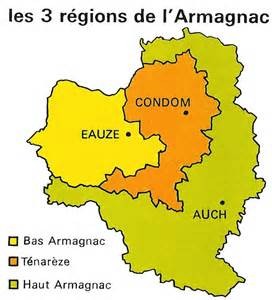

There are three armagnac crus, the smallest is Bas Armagnac. However, whilst it is the smallest in land mass, it is the largest armagnac production region making around 57% of all the armagnac produced. The department is in the north west of the region, closest to the Atlantic where, millions of years ago, the sea washed in sandy and silty soil which now produces some of the finest armagnacs. These fine spirits are fruity, light and delicate and regarded as the best armagnacs in the region. The main town in the Bas department is Eauze, a small market town where the BNIA can be found.

To the East of Bas is the second cru of armagnac known as Ténarèze. The department is slightly bigger than Bas and in the centre lies the town of Condom with its beautiful buildings and Armagnac museum. The cru comprises about 40% of all the armagnac vineyards and the armagnacs produced here tend to develop much slower than those in Bas. The clay and limestone soil produces rich and fruity spirits which are often used whilst relatively young to make generic blends.

The largest cru is Haut Armagnac. It surrounds Ténarèze on three sides, north, east and south and the main town is Auch which is in the centre of the region. The cru is often referred to as white armagnac as the soil contains an abundance of limestone. The viticulture was developed here in the 19th century to meet the high market demand but has since dwindled away to only a few producers who make largely uninteresting armagnacs.

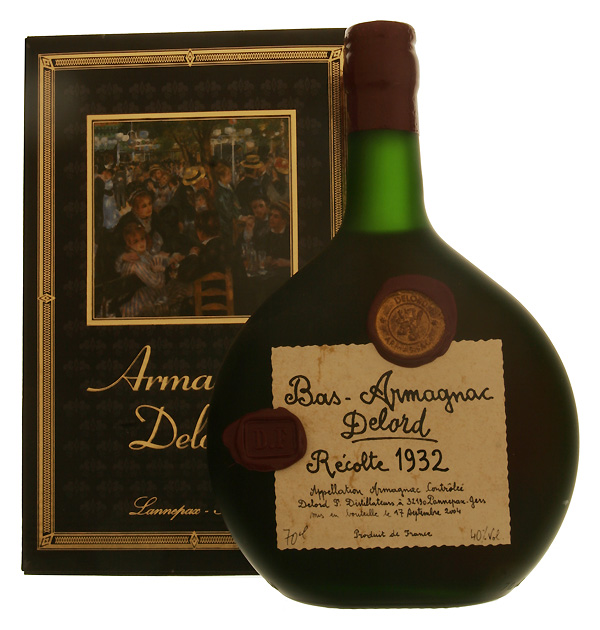

Whilst armagnac is not so well known as its big brother cognac, it is a beautiful spirit. It has many rich and fruity flavours, the most common being prune, which can often be identified in the Delord range. They are one of the older producers in the region situated in the top cru, Bas Armagnac.

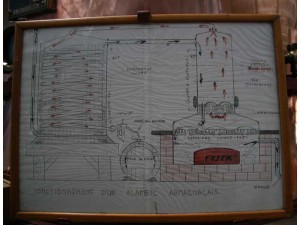

Armagnacs are the earliest examples of distilled wines known in France. Traditionally they are made using the Folle grape although others, including Colombard, Ugni Blanc and even more recently, the Baco all contribute to its flavour. Initially distillations were on a pot still but by the 19th century the continuous still was more highly favoured. The distillation process of armagnac allows the spirit to be distilled at a much lower alcohol content range than that of its big brother cognac, produced 100 miles to the north. The lower range produces a greater fruitiness (but less refined) flavour in the spirit.

Armagnacs are the earliest examples of distilled wines known in France. Traditionally they are made using the Folle grape although others, including Colombard, Ugni Blanc and even more recently, the Baco all contribute to its flavour. Initially distillations were on a pot still but by the 19th century the continuous still was more highly favoured. The distillation process of armagnac allows the spirit to be distilled at a much lower alcohol content range than that of its big brother cognac, produced 100 miles to the north. The lower range produces a greater fruitiness (but less refined) flavour in the spirit.

Even with this reduced vineyard area, demand and production in the 1960s started to grow again. Sales in the domestic market grew faster than exports and mainly comprised young, cheap brandies. This resulted in little being left in the barrels to sell in later years as vintage armagnacs but interest in the fruity brandy had begun to develop. By the start of the 1980s production had risen to nearly 35,000 hectolitres of pure spirit, a level that by 1990 had nearly doubled to 60,000 hl pure. The Armagnaçais had started to realise the many benefits of their spirit over their competitors.

Even with this reduced vineyard area, demand and production in the 1960s started to grow again. Sales in the domestic market grew faster than exports and mainly comprised young, cheap brandies. This resulted in little being left in the barrels to sell in later years as vintage armagnacs but interest in the fruity brandy had begun to develop. By the start of the 1980s production had risen to nearly 35,000 hectolitres of pure spirit, a level that by 1990 had nearly doubled to 60,000 hl pure. The Armagnaçais had started to realise the many benefits of their spirit over their competitors.