David on Technical Topics – Cognac Distillation, The Wine Reduction

Cognac Distillation – The Wine Reduction

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the brandies produced in the Charente were reduced by distillation as this made them easier to ship abroad. The risk of low alcohol wines going off before they reached their destination was avoided and the intention was to cut them back with water before they were consumed. But the Cognaçaise soon found that keeping the strong wines in barrels changed them for the better and so they started to learn the skills of distillation.

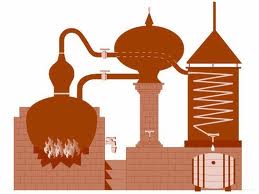

The basic concept of distillation is that you boil the wines, collect the vapours that escape and then allow them to condense back into a liquid. It sounds ridiculously simple but there are many things that can go wrong unless the process is carefully controlled.

Cognacs are double distilled, that is to say that after the first distillation the wines are re-introduced into the still to be distilled a second time. During the process most of the chemical changes in the wine occur, at a temperature of less than 40 degrees, during the first distillation. Careful consideration must therefore be given as to that which is put into the still. Most modern day cognac distillations include the lees; this is anything but the juice. Most lees used consist of the pulp of the grape. In some cases the skin is also added but the pips and stalks are not as they will introduce an unacceptable bitterness. Some purists will filter out the lees and distil just the juice but this provides a cognac with less flavour and ultimate complexity. It is the yeast in the wine that contains esters which enrich the cognac and provide more flavour.

The first distillation is regarded by many as the most important as this is when the essential qualities of the fruit are extracted. The slower the cooking the more thoroughly the flavour in the wine is absorbed into the resulting brouilli (a cloudy and non-descript liquid at a strength of between 28 – 32 degrees). The brouillis is undrinkable and it is quite impossible at this stage for the distiller to determine the qualities of the final liquid.

The second distillation is known as the Bon Chauffe (good heating). Not all the newly distilled liquid or eau de vie is used. The first quantity, of around half a percent, is known as “the heads” and is discarded as it is too strong and will probably clog with some of the solids. The last part of the distillation, “the tails”, will be too weak. They can be re-introduced into the still but this is in itself a major decision. If the tails are used they will be distilled twice more and will create a level of neutrality in the final spirit. The middle part, which is probably greater than 95%, will be stored in new barrels for a few months to provide the new spirit with an initial boost of flavour and colour. The distillation range of the second boiling must be between 67 – 72.4 degrees, above this range the spirit will be burnt and below it there will be insufficient refinement in the final cognac.

To read more Technical Topics go to our Brandy Education page.